Mitigating gender bias in recruitment

Mitigating Gender Bias in Recruitment

In recognition of International Women’s Day, Victor Reis, Consultant and Chartered Occupational Psychologist at Alumni discusses the facts around gender bias and how best to mitigate against it within the context of recruitment. He discusses the difficulty of overcoming bias, and the importance of changing processes and methods to support equality rather than relying on trying to change how people think.

The struggle for gender parity

Whilst society is becoming more progressive, the movement towards gender equality has in reality slowed down over time, as shown in the Gender Inequality Index tracked in the UN Human Development Report[1]. There is even evidence that the pandemic has led to some metrics going into reverse[2]. Whilst many analyses are based on binary gender information, we recognise that the issues faced hold true for non-binary as well as transgender individuals.

Despite growing awareness around the ’glass ceiling’, and gender equality mandates within governance and corporate policy, the 2020 Mercer report ’Where Women Thrive’ clearly shows that women remain very underrepresented both at leadership level and within the C-Suite.[3]

Recognising progress and measuring improvements

It is important to recognise that EDI has come a long way. In addition to increased legislation to support it, many companies introduced internal training programmes aimed at creating awareness of unconscious bias and recruitment practices. These initiatives led to ‘difference’ being more fully and positively represented in broadcast media. Yet, the status quo of diversity remains largely unmeasured within business, primarily because HR processes are not fully integrated and too many initiatives are driven without a cohesive employee journey narrative from recruitment to offboarding. How can organisations know that they are improving without an accurate baseline?

Many organisations have awareness forums and support groups for minority representations in their business and these can be useful tools to raise the profile of EDI and kickstart conversation. Unfortunately, they are isolating by definition and generally lack the power to make decisions and influence policies. The key performance indicators for EDI are too many, widely dispersed and sometimes conflicting at different steps in the employee journey.

To achieve a more comprehensive narrative, companies will need to move beyond a focus on diversity for its own sake, and towards providing a safe, open and inclusive work environment that is underpinned by a sense of belonging for all employees, at all steps in their journey. Business has significant power to change and contribute to a more open, diverse and inclusive society but only by starting from within.

So why are efforts going unrewarded? In short, the answer lies in the perpetual existence of gender bias and society’s apparent difficulty to effectively attenuate or negate its effects. Most of our daily decisions are based on quick, heuristic and largely unconscious information. This is great for the survival of the species but means that those decisions are vulnerable to stereotyping and bias.

The evidence for gender bias in business

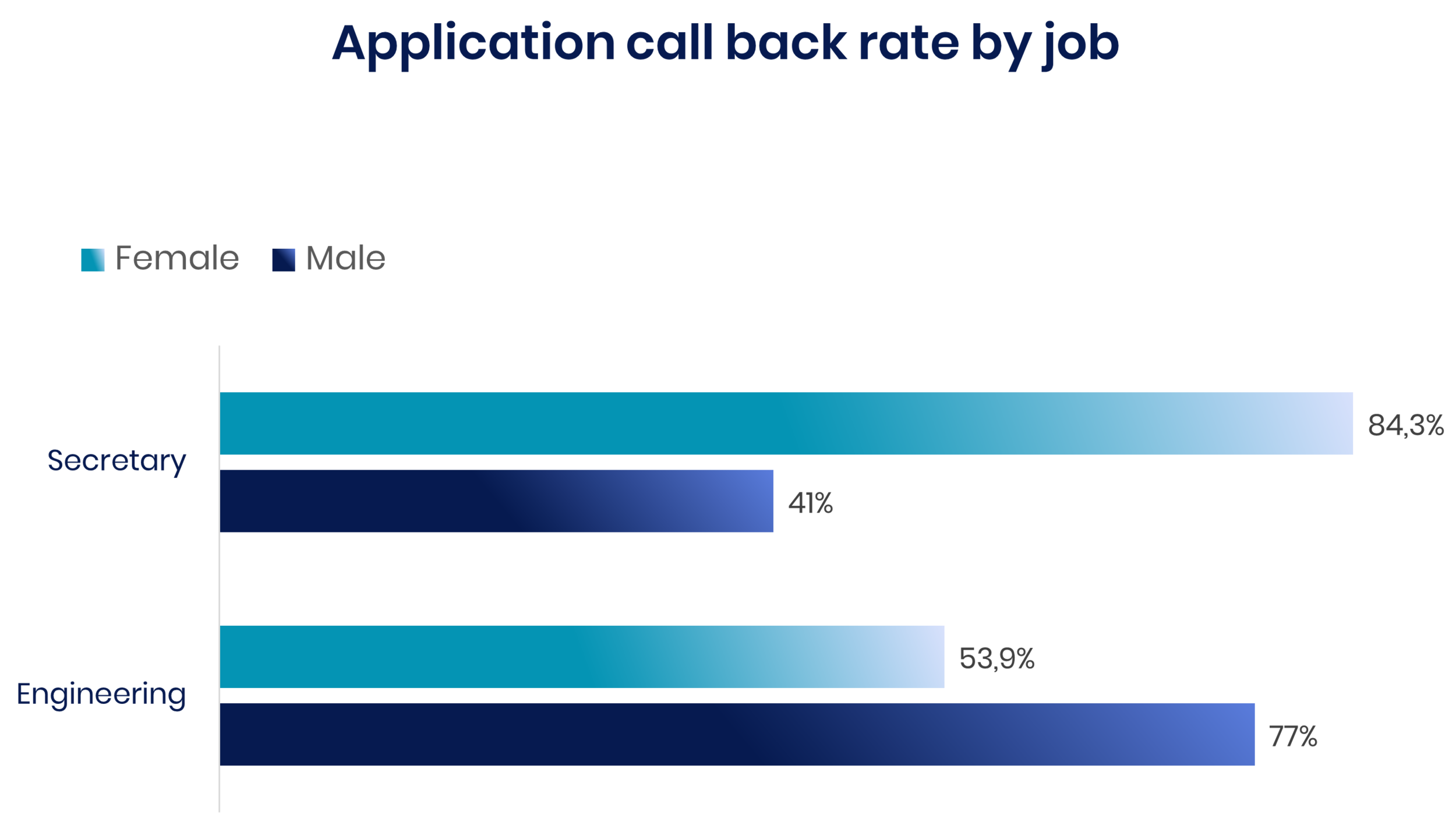

There is a plethora of studies that clearly show the realities of progressing in a career as a female. In 2006, Riach & Rich tested for gender discrimination in hiring by sending carefully matched applications to open job vacancies and altering the gender on the application[4]. Results reinforced not only the existence of gender discrimination, but that the effect was even more distinct for stereotypically gendered jobs such as secretarial or engineering roles. It could be argued that if discrimination works both ways, why is it a women’s issue? While both men and women suffer from stereotyping, it is not a zero-sum equation. Positions that are gendered as male do to a much larger extent involve leadership and high-status roles, so the gender-specific discrimination has a greater negative impact on women.

In 2012 Moss-Recusin et al. demonstrated how gender bias exists for students applying for scientific studies by simply changing names on applications to typically male or female ones. The applications gendered as female got significantly lower ratings for competency, hireability, and likelihood of receiving mentorship[5]. Sadly, this bias was as evident in female members of the faculty as it was for the males.

The propensity for recruiting in one’s own image has long since been evidenced and in a world where the majority of leaders are male, this spells bad news for gender parity. Furthermore, pro-male bias has also been clearly demonstrated for work performance when males are the sole raters.[6]

All this, before we even begin to look at the effects of parenthood on a career[7]. So far – so depressing, but what can we do to mitigate these effects and make females truly equivalent in recruitment eyes?

Change the processes rather than people

Unconscious bias training is used by many companies to try and tackle the inequality dilemma. Intuitively it makes sense; if we can educate people around how we are all biased, and how that perpetuates inequality in the workplace, then that should lead to a significant positive behavioral change. However, research shows that in practice we quite quickly fall back into our old ways of thinking when left to our own devices after the training.

To make lasting change we need to focus less on changing people, and more on designing the right processes, systems and environments that support gender equality. Some major areas to consider are listed below.

Succinct and specific role requirements

A job description should contain sufficient information to describe its major responsibilities and essential functions as they exist today. It should provide the information necessary to classify the position and focus on key requirements – less is more. Keeping focus on the essentials and not taking a copy/paste approach increases the chances for a successful and diverse recruitment.

Ensuring that job requirements for a given role are short and specific to a given role, is not only important in general for successful recruitment, but it may also have a positive gender effect: as a group, women report that they feel the need to “tick more of the boxes” in order to apply for a job. By avoiding unrealistic “extra everything” job ads you decrease the chance of qualified women not applying.

Blind screening

Blind screening is about making candidates anonymous – removing details from applications or CVs that reveal details that may introduce prejudice including gender. It makes it easier to make objective decisions about a candidate based on skills, experience and suitability without the distraction and potential damage of bias.

Nearly all hiring decisions will involve an in-person interview. But take a step back in the process, and anonymised applications and test procedures can introduce a greater degree of objectivity and help ensure that all candidates are competing on a level playing field. With the opportunity to be assessed only on qualifications or skills, the best candidates for a role can be identified.

Selection and evaluation methods that reliably predict work performance

Psychometric testing can measure a number of attributes including intelligence, critical reasoning, motivation and personality profile. This type of testing can provide your recruitment strategy with a highly reliable method for selection, especially when interview processes are fairly subjective and susceptible to bias.

General Mental Ability is one of the best predictors of future performance and standardized, valid, psychometric tests that measure aptitude in relevant areas of the role, can provide a level playing field.

Longer informal shortlists

What we see and experience, whether right or wrong, can form unconscious assumptions within us about how things should be. For example, with the prevalence of men in managerial and leadership roles, there can be an assumption that men are more suitable for those roles than women. Consequently, when people think about candidates who would be a good fit for those jobs, male candidates are more likely to come to mind over equally qualified female candidates.

Informal shortlists pose a particular barrier to gender equality because they dually suffer from the systemic bias of informal, network-based recruitment and from the implicit bias of selecting top-of-mind candidates in gendered roles. One promising solution to this dilemma is to increase the length of the informal shortlist. Studies show that the number of female candidates listed was 33% higher in an extended shortlist compared to an initial shortlist. Whereas as an initial list of three contained a 1:8 ratio of women to men, an extended list of six contained a 1:6 women-to-men ratio.[8]

Fair interview processes

A gender diverse interview panel can reduce the risk of unconscious gender bias. If possible, it is a good idea to extend this strategy to have a fair mix of cultural diversity and age range when conducting a series of interviews.

Adding structure to an interview by having a series of standardised questions that are used uniformly across the whole process, makes it easier for the interviewer to compare each candidate applying for the job fairly. Having guidelines to record and interpret responses during an interview is imperative. It’s also a good idea to identify the preferred answer to each question in order to make scoring fairer across the interviewee group.

Review recruitment practices

Our gender does not define us; we all have unique skills and personalities that should be celebrated. However, diverse organisations are more innovative, creative and profitable and recruiters should do all they can to counter gender inequality where they find it, for the good of the organisation and wider society.

Whilst helping recruiters become aware of their bias is a useful first-step in boosting gender parity, reflecting on and changing recruitment processes will bring about the best sustained change towards creating an inclusive and equitable recruitment practice.

References

[1] https://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii

[2] http://covidacademics.co.za/Uploads/docs/The-impact-of-the-coronavirus-pandemic-on-gender-equality.pdf

[3] Mercer When Women Thrive Report 2020

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4908229_An_Experimental_Investigation_of_Sexual_Discrimination_in_Hiring_in_the_English_Labor_Market

[5] Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Corinne A. et al. PNAS October 9, 2012 109 (41) 16474-16479;

[6] Evaluating Gender Biases on Actual Job Performance of Real People: A Meta-Analysis1, Chieh-Chen Bowen,Janet K. Swim,Rick R. Jacobs

[7] M José González, Clara Cortina, Jorge Rodríguez, The Role of Gender Stereotypes in Hiring: A Field Experiment, European Sociological Review, Volume 35, Issue 2, April 2019, Pages 187–204,

[8] https://hbr.org/2021/02/research-to-reduce-gender-bias-in-hiring-make-your-shortlist-longer

Alumni

Alumni has more than 30 years’ experience in recruitment, leadership assessment and development and we are passionate about diversity and inclusion. We also practice what we preach within our own organisation. We have some of the most diverse networks of potential candidates across many geographies. We understand fully how to maximise inclusion at all levels of within the organisation and particularly in the recruitment processes. We have tried and tested, formal methodologies for creating inclusive approaches to attraction, selection and onboarding. We also work to develop the leaders of both the present and future, with assessment, training and awareness programmes. If you would like to explore how to make your organisation more diverse, more inclusive and ultimately, more successful, then please get in touch.